As usual, I’m leaving it to others to dissect the second Presidential debate in terms of policy and politics and instead focus on what we can learn from that exchange to become better critical thinkers and effective communicators.

As readers of Critical Voter well know, the most important question that needs answering in order to understand the dynamic of a persuasive presentation is “Who is the actual audience?”

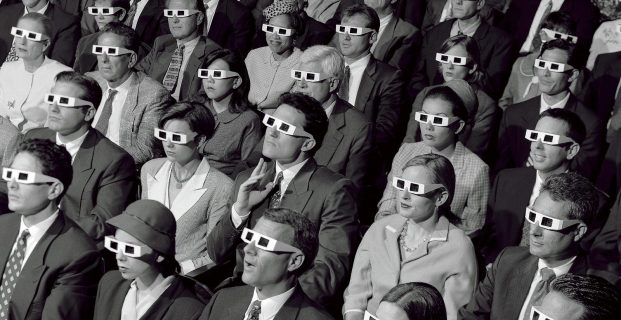

The second debate used a Town-Hall style format, which tried to create an intimacy one sees in smaller (often untelevised) small-group meetings that take place earlier in the campaign season. As noted here, appearances candidates made at VFW halls before the New Hampshire primary actually involved personal interaction with audience members, if only because those were the only people participating in or viewing the event.

But in a televised general election debate being viewed by over a hundred million people, that wider audience obviously takes precedent over the people in the room, who must also stand in line for attention behind the media – another audience both candidates are appealing to for stories of victory and momentum.

In the past, Presidential candidates did a reasonable job trying to make their appeals to these wider audiences appear as answers to questions posed by the “real people” standing in front of them. But another benefit of this year’s race between one candidate with so-so rhetorical skills (Clinton) and another candidate who eschews formal political oratory altogether (Trump) is that it gives us outsized examples to learn from (much like we dissect large frogs to learn anatomy vs. tiny newts).

For instance, would anyone watching that debate think for a moment that either candidate took the slightest interest in any of the questions being asked by the audience, much less the human beings asking those questions?

In Town-Hall debates that took place during previous election, candidates more skilled in rhetorical technique used a combination of (1) thanking the questioner by name; (2) complimenting him or her on the importance and insightfulness of their query, and then (3) paraphrasing the original question for the wider audience (both in the room and on TV) with subtle changes designed to link the question to a talking point the candidate already had prepared in advance.

Those who viewed the debate through the lens of rhetorical craftsmanship will have noticed that neither candidate took the trouble to go through these steps beyond the perfunctory. In fact, few answers to any question veered off the main goal of each presidential aspirant: to move the camera back to the negatives associated with their foe (the only dynamic that seems to be impacting this year’s presidential race in any way).

This doesn’t make Clinton and Trump any more or less disinterested in close-at-hand human beings than were previous aspirants for the Oval Office. After all, candidates Obama, Romney, McCain, Bush, Kerry and Gore all went through the rhetorical motions of trying to appear interested in what flesh-and-blood people were asking them while actually planning how to inject their pre-prepared zingers, gotchas and talking points into their response. In fact, one has to go back to Hillary’s husband to find someone able to pull off this trick without coming off as insincere.

Bill Clinton’s great political gift was his ability to generate an ethos bond with people right in front of him, giving them the impression that he valued their opinion and would prefer talking to them one-on-one vs. being anywhere else in the world. And he was able to generate this kind of chemistry, even while doing what every other presidential candidate has done in the television age: communicating his preferred message to an unseen audience beyond the debate stage.

In contrast, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump gave the impression that the entire experience was an ordeal to get through without making a blunder, vs. an occasion to spend time answering the honest questions of real voters.

Perhaps it is in this disinterest in creating a genuine ethos bond with people hungry to feel some sort of personal connection to their potential president that has created historic negatives for both candidates, rather than this tax return or that e-mail server.

Discuss…