This week’s storm got me thinking about a little parody I penned during the last Presidential election that went something like this:

“It’s been six days since the Reticulan battle fleet entered Earth orbit, and today this unearthly race of reptilian shape shifters issued their demands that Earth submit to their will and surrender mankind’s freedom, mineral wealth and women,” announced Katie Couric, wearing the metal bikini required of all concubines of the Reticulan High Command. “As yet, we have had no definitive statements from either the McCain or the Obama camp regarding this latest twist to an already dramatic 2008 Presidential campaign.”

Meanwhile, CNN’s “Best Political Team,” broadcasting from an underground bunker in an unknown location, wondered how the Reticulan’s recent killing of every living thing in Europe might impact the dynamic of this race. “Obama was already four points up in the polls before the alien invasion fleet blew out most of the nation’s communication grid,” said James Carville, his voice slightly muffled by the helmet of his radiation suit. “I don’t see why those numbers can’t hold until Election Day. “I disagree,” replied David Gergen, having recently escaped from the alien’s lunar mining colony. “During times when the country perceives itself to be under a threat, Americans instinctively look to experience, and, fair or not, John McCain is seen as having been tested in battle, even if his time in Vietnam did not involve atomic laser cannons.”

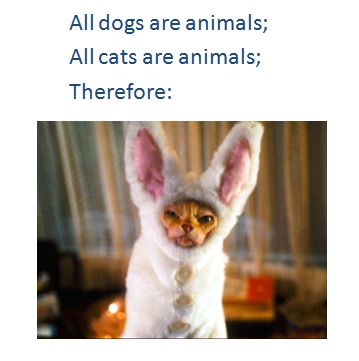

At the time, I used this gag to illustrate the irony inherent in the concept of the “single issue voter,” someone who feels so passionate about a single subject that they are willing to cast their presidential vote based on a candidate’s stand on this one issue alone. The issue might be domestic (such as abortion), or international (such as support of Israel or Cuba, or opposition to the war in Iraq).

Such voters tend to be criticized due to the perception that their obsession with a single cause blinds them to the many other issues and decisions that need to be weighed with regard to a Presidential choice. But this analysis misses the point that, for many people, a single issue is not thought about in isolation, but rather provides a frame through which the candidates and other issues are judged.

For instance, those who feel passionate about abortion do not tend to think about this issue and nothing else. Rather, an abortion stand becomes shorthand for a framework of values (self-labeled as “Pro-Choice” and “Pro-Life”) which apply to voters’ (and candidates’) positions on a great many issues also seen as moral questions.

Similarly, anti-Castro Cubans are often seen as the quintessential single-issue voters, and yet their opposition to the Castro regime is built into a wide-ranging anti-Communist ideology by which they have historically judged candidate’s against a number of foreign policy questions.

Those that accuse others of voting based on narrow interests fail to perceive the irony that voters who are allegedly looking at the “big picture” are (as illustrated in the parody at the top of this piece) capable of boiling any and all issues into a single question of who to vote for in the Presidential race. For partisan voters also have a frame they use to understand the world: a frame in which the issues of the day get filtered through the ultimate question of whether it helps “my guy” or his opponent.

Such frames are normal, indeed required if we are to make sense of the world. For while we may espouse an ideal in which each and every issue is looked at on its own merits and analyzed based on reason alone, such an ideal is only suitable for computers and Vulcans, not for human beings (and, as we talked about in a previous podcast, even Vulcans do not live by this ideal).

Here on earth, emotion and human connection (pathos and ethos) will play a role in both our decisions and the fact-gathering and logical analysis (logos) that goes into those decisions. And the frames we use to choose our facts and make our decisions (be they partisan frames or something else) are built on the natural tendency to associate with communities and prioritize some issues and concerns over others.

Our challenge comes not from having such frames (which are necessary to see the world as something other than a random set of occurrences), but to ensure those frames are not so rigid that they cause us to make errors, ignore important matters, or refuse to see any part of the world outside of how it fits into this frame.

This week’s storm is a good case in point. One cannot help but remember that Hurricane Katrina was part of the bill of indictment against George W. Bush, which meant that even before the flood waters had receded from places like Louisiana and Mississippi, we were talking about that last storm of the century in terms of who it “helped” and “hurt” politically.

Republicans hoped that the oil spill that impacted the Gulf in 2010 would provide a chance to tie a subsequent disaster around a Democratic President’s neck, and I anticipate that once the initial shock over this week’s hurricane has been absorbed, talk will increasingly focus on Hurricane Sandy and the 2012 Election (notably the success or failure of Federal recovery efforts mean for next Tuesday’s Presidential contest).

This is where tools like the Principle of Charity become particularly useful. For if you’d become enraged if someone from “the other side” started using a natural disaster like Sandy for political gain, you should also feel embarrassed (even a bit ashamed) if “your side” started doing the same thing (emotions that would likely come naturally if you or a loved one was directly impacted by the storm and had to watch partisans bicker while you and those you cared about suffered).

And here we have a perfect example of how human emotion (even ones we normally don’t consider constructive, such as anger, embarrassment and shame) can actually be beneficial to our thinking, by providing us an alternative frame (in this case the frame of someone suffering who we should naturally sympathize with) vs. a frame that only cares about how this or that issue impacts the polls.