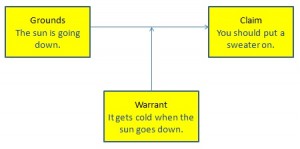

Just as we looked at a negative ad directed at Mitt Romney to see how Toulmin argument maps work, we’ll now look at an ad attacking President Obama to see how to determine and analyze the underlying argument using a traditional syllogism.

The ad we’ll be using (shown above) is called “Doing Fine” and gets its name from an Obama press conference quote where, among other things, he stated that “the Private sector is doing fine,” an assessment the creators and approvers of the ad clearly disagree with.

As I mentioned in the previous attack ad analysis, despite the manipulativeness of such spots (with their ominous background music, pathos driven narratives, and the like), the good things about negative ads is that chances are pretty good a genuine argument can be found within them. So from a critical thinking perspective, they are better material to work with than TV spots based solely on praise and puppy dogs.

Looking over “Doing Fine” a few times, one can discern an argument that goes something like: “President Obama says the private sector is doing fine when, in fact, it is not doing well at all. Therefore, the President is out of touch with economic reality.”

This message is actually an enthymeme, which I defined yesterday as a standard three-part syllogism (two premises leading to one conclusion) where one of the premises is implied, but not stated outright. So if we were to extend this enthymeme to include the unstated premise, it would look something like:

Premise 1: President Obama says the private sector is doing fine when, in fact, it is not doing well at all.

Premise 2: Anyone who claims the private sector is doing fine when it actually is not is out of touch with economic reality.

Conclusion: President Obama is out of touch with economic reality.

Linked to this argument is another argument that says anyone so disconnected from economic reality does not deserve to be President. But, for now, we’ll just focus on the primary syllogism shown above to see if this argument holds up.

The first thing you should notice is that this syllogism is, in fact, valid in that if you accept the premises, then you must accept the conclusion. Since this syllogism is a result of our own translation of the original material into premises and a conclusion, I suppose we could have made an effort to translate it in a way that makes the argument invalid. But as we’ll see, there is more to be gained by doing our best to construct a valid syllogism out of source material and then use that to analyze the argument for soundness.

If you recall, a syllogism can be valid, but still unsound if the premises upon which the argument based are false or at least insufficient to hold up their end of the argument.

In this case, the premise that is most vulnerable is the first one since it can easily be challenged by (1) asking if the “Doing Fine” quote accurately reflects the President’s beliefs and (2) determining if the private sector is, in fact, doing fine or not.

Regarding action (1), if we look at the original statement in its full context, I think it’s fair to claim that President Obama demonstrates a comfort level with the current state of the private sector economy. However, it is also clear that he understands the struggles the private sector has done through over the last 4-5 years. And, more importantly, he is making a case that other economic issues (the crisis in Europe, challenges in the public sector) are more problematical (and thus need more attention) than problems in the private sector.

So if we look at the original first premise of the argument drawn from the “Doing Fine” ad, a more charitable description might say “President Obama thinks the private sector is doing better than other parts of the economy and thus needs less attention from government.”

Moving onto action (2), the TV ad provides just three pieces of evidence (shots of newspaper clips discussing fears associated with slow job growth). But these sources are problematical, given that they are just snippets from three newspapers (only two of which are identifiable); and that none of these stories clearly focus on the subject at hand, which is the current state of the private sector economy.

Further examination of these sources might show that they do support the original ads assertion of a struggling private economy. But even if they do, they do not provide sufficient evidence to support the claim that the private sector is doing so terribly than anyone who says otherwise is out of touch with reality.

Fortunately, the same Internet that lets us look at both the “Doing Fine” video as well as the original press conference the quote was drawn from in their entirety whenever we like, also allows us to perform our own research regarding the state of affairs with the private sector (with how to perform such research being the subject of an upcoming podcast).

But if we assume that the private sector is challenged but not collapsing and combine it with what we concluded from watching the original press conference, I think it’s safe to say that the original attack ad provides an argument that is of unquestionable validity, but questionable soundness.

This does not mean that any assertion questioning the President’s connection to economic reality is inherently unfair or illegitimate. It simply means that those posing such assertions need to present more evidence than they do in the “Doing Fine” attack ad to convince those of us who have been equipped by Aristotle to not let other people do our thinking for us.