Most of us probably expected an election similar to ones we’ve experienced in the past: a rowdy primary that finally settles down to each party picking a Senator or Governor (maybe a Congressman) whom the parties could rally around before going into battle in the Fall. If there were to be any surprises, these too would come in familiar forms, such as an unexpected gaffe during a debate, or maybe some “gatcha” video being released close to Election Day.

But surprises have a way of, well, surprising us. And now that it looks like at least one party will be led by a man with no political experience whatsoever, it’s probably time to turn the critical thinking skills you’ve been developing towards figuring out what on earth is going on.

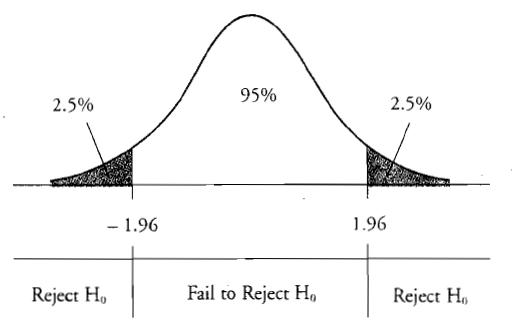

One technique I didn’t bring up in Critical Voter is hypothesis testing, the process of proposing an explanation which is then put to tests designed to see where a proposed answer might fail. This is how the scientific method is supposed to work and the wild success of science in solving problems over the last several centuries has led to the adoption of scientific methods (or at least a scientific vocabulary) by other fields such as business and education.

Applying this technique to our current political scene, the simplest hypotheses to explain why the Republican Party nominated a candidate like Donald Trump are partisan ones. For Democrats, Trump’s nomination demonstrates that Republicans are a bunch of dangerous simpletons who have proven themselves unfit to govern. For Republicans (at least the substantial segment of them who decided to choose Trump as their leader), what the nation needs is an outsider ready to “tell it like it is” and “take the fight to the enemy,” characteristics more important than governing experience (especially since such experience hasn’t stopped previous candidates from losing to Democrats).

Given that one of these two hypotheses is likely embraced by a majority of the nation’s voters, neither be dismissed just because they are self-serving or the result of circular reasoning. Remember that our job as critical thinkers is to flag when an argument (especially one we might make or be inclined to accept) might be influenced by confirmation bias, but not to dismiss such biased arguments out of hand.

For example, that line about Republicans being “unfit to govern“ was drawn not from Democratic talking points, but from an editorial written by Conservative Republicans decrying the disaster they claim a populist uprising will cause their party. So if Republicans are saying that their own party’s primary voters are acting irresponsibly, wouldn’t that support Democratic contentions that their rivals have uniquely gone off the rails?

Perhaps. But if we allow more data to influence our thinking, there is evidence that an acceptance of passion over experience (or pathos over logos), as well as radical disgust with the status quo is something you can find across the political spectrum. Bernie Sanders is obviously not as wild a figure as is Donald Trump. But it’s worth noting that of the 20+ candidates who first threw their hats into the ring last year, four out of the five who were left standing last week (Clinton, Trump, Sanders and Cruz) could all be described as polarizing, or at least far more polarizing than the dozen-and-a-half “conventional” candidates the electorate rejected.

Pulling back a bit further, the passions released this year seem to have led to acceptance of political tactics that dance around the line between persuasion and coercion. Protestors (or mobs, defending on whichever connotation serves someone’s purposes) preventing rivals from speaking or shouting candidates off the stage has not yet become a regular fixture of the campaign landscape. But enough of it is going on across the political spectrum to indicate that even Democrats smugly condemning the imbecility of the rival party might be one skilled demagogue away from going down the same route.

So if one-sided partisan explanations might not fit with this wider data, what else could explain why today’s politics looks the way it does? We’ll continue next time by looking at a hypothesis favorited by much of the media which I will dub the Politics of Anxiety.